VM networking with NetRelay

Virtual machines are powerful tools for development, testing, and deployment—but their

networking can be a headache. Especially when you're trying to connect VMs across hosts,

simulate complex topologies, or avoid root privileges. That’s where netrelay comes in:

a lightweight utility I built to relay traffic between QEMU VMs, Linux bridges, and other

endpoints with minimal friction.

In this post, I’ll walk through how netrelay works, why it matters, and how it integrates

with libvirtd-managed VMs to create flexible, user-space networking setups.

You can find the source code on Github.

Motivation: Why Build netrelay?

QEMU offers several networking modes—user, tap, socket—but they each come with trade-offs. Socket mode is great for point-to-point links, but it’s fragile across hosts and lacks reconnection logic. Bridging requires root access. And user mode is too limited for realistic scenarios.

While QEMU’s UDP mode works well for VMs on the same host (via loopback), it becomes unreliable across hosts due to MTU fragmentation. Large Ethernet frames may be split into multiple UDP packets, which can be dropped or reordered. TCP avoids this but introduces tunnel setup timing constraints.

I needed something that could:

- Connect VMs across hosts without root

- Support both TCP and UDP transports

- Integrate with Linux bridges and TAP devices

- Work around QEMU’s limitations (e.g., TCP tunnel setup timing)

- Be scriptable, testable, and robust

Thus, netrelay was born.

What Is netrelay?

netrelay is a relay utility for QEMU VM traffic. It forwards Ethernet frames between endpoints

using TCP, UDP or Linux bridge interfaces. It can run in two modes:

- Point-to-point: Like a virtual crossover cable

- Server mode: A dumb hub that distributes frames to all connected clients

It’s compatible with QEMU’s -net socket mode and uses QEMU-style framing over TCP for

interoperability.

How It Works

TAP Devices

netrelay uses TAP devices, which operate at Layer 2 and handle full Ethernet frames.

This is essential for VM networking, where MAC addresses, ARP, and non-IP protocols matter.

TUN devices only support IP packets and are unsuitable for this use case.

Frame Encapsulation

- TCP: Uses QEMU-style framing—each frame is prefixed with a 4-byte network-order

length header.

This framing ensures correct frame boundaries over TCP’s stream-oriented transport.

- UDP, bridge: Uses native framing from the transport or interface.

Endpoints

You can specify endpoints in flexible ways:

-→ stdin/stdout (for testing)ip:port→ TCP clientlisten-port:ip:send-port→ UDP peerbridge→ Connect to a Linux bridge via TAP

Examples

Connecting Two VMs via TCP

Let's say you have two VMs on separate hosts. You want them to communicate over a TCP tunnel.

On one of the hosts run this:

netrelay -l 12345Assuming this host has IP address 10.0.0.1.

Configure the VMs with the following XML settings:

<interface type='client'>

<mac address='44:d2:ca:c2:37:1b'/>

<source address='10.0.0.1' port='12345'/>

<model type='virtio'/>

</interface>This sets up a tunnel between the two VMs:

As long as netrelay is running, the startup order of VM A and VM B does not matter. Also unlike emulation over UDP, this works with jumbo frames, if needed, across different hosts.

Connecting a VM to a bridge

On a remote system we have a bridge to a physical device named br0. Start as root:

netrelay -l 12345 br0or

sudo netrelay -l 12345 br0Assuming this host has IP address 10.0.0.1.

Configure the VMs with the following XML settings:

<interface type='client'>

<mac address='44:d2:ca:c2:37:1b'/>

<source address='10.0.0.1' port='12345'/>

<model type='virtio'/>

</interface>This connects the VM to the bridge:

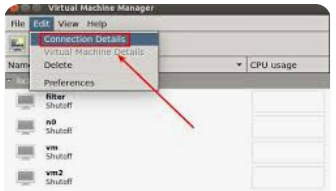

Only the netrelay process needs root privileges. Whereas the whole libvirtd stack can

run as a normal user.

Future Plans

Here are some possible improvements:

- Optional MAC filtering or switching logic

- Loop detection and mitigation

Conclusion

netrelay is a pragmatic solution to a real-world problem: how to connect VMs flexibly,

securely, and without root. Whether you're building test clusters, simulating networks, or just

trying to get two VMs to talk, it gives you the tools to do it cleanly.